Those innocent spice jars sitting in your cupboard don’t do much to reveal their incredible history. But did you know that nutmeg was once worth more by weight than gold? That in the 16th century, London dockworkers were paid their bonuses in cloves? That in 410 AD, when the Visigoths captured Rome, they demanded 3,000 pounds of peppercorns as ransom?

In its day, the spice trade was the world’s biggest industry: it established and destroyed empires, led to the discovery of new continents, and in many ways helped lay the foundation for the modern world.

Spices, which today are inexpensive and widely available, were once very tightly guarded and generated immense wealth for those who controlled them. The spice trade began in the Middle East over 4,000 years ago. Arabic spice merchants would create a sense of mystery by withholding the origins of their wares, and would ensure high prices by telling fantastic tales about fighting off fierce winged creatures to reach spices growing high on cliff walls.

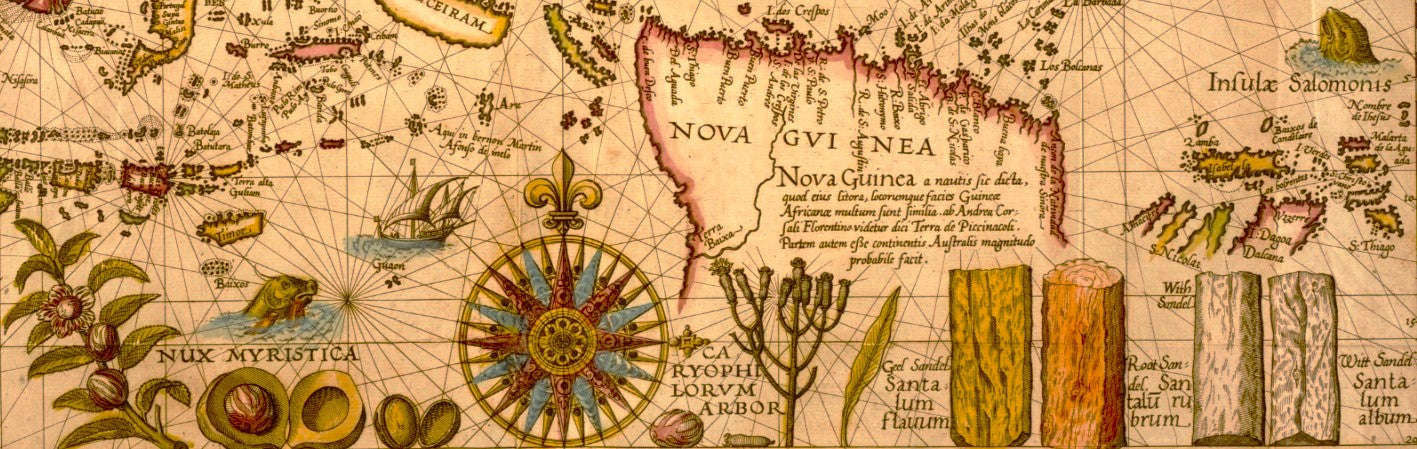

Initially, the spice trade was conducted mostly by camel caravans over land routes. The Silk Road was an important route connecting Asia with the Mediterranean world, including North Africa and Europe. Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in the development of the great civilizations of China, India, Egypt, Persia, Arabia, and Rome.

The Roman Empire set up a powerful trading centre in Alexandria, Egypt in the first century BC and was in command of all of the spices entering the Greco-Roman world for many years. In another example of the historical value of now-common spices, Roman soldiers of the time were frequently paid in salt, a practice that led to the word “salary” and the phrase “worth his salt.” Over the following centuries, countless groups battled for control of the spice trade. Eventually, in the mid-13th century, Venice emerged as the primary trade port for spices bound for western and northern Europe. Venice became extremely prosperous by charging huge tariffs, and without direct access to Middle Eastern sources, the European people could do little else but pay the exorbitant prices they were charged. Even the wealthy had trouble paying for spices, and eventually they decided to do something about it.

In the 15th century, the spice trade was transformed by the European Age of Discovery. By this time, navigational equipment was better and long-haul sailing became possible. Rich entrepreneurs began outfitting explorers in hopes of circumventing Venice by discovering new ways to reach the areas where spices were grown. There were many voyages that missed their targets, but several of them ended up discovering new lands and new treasures. When Christopher Columbus set out in search of India, he found America instead, and brought back to Spain the fruits and vegetables he found, including chiles (he called them “peppers”, perhaps to soothe his disappointment at not finding peppercorns, and the term “chile pepper” persists to this day).

The first country that successfully circumnavigated Africa was Portugal, and in 1497 four vessels under the command of Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope, eventually sailing across the Indian Ocean to Calicut, India. This success marked the beginning of the Portuguese Empire. Spanish, English and Dutch expeditions soon followed, and the growing competition sparked bloody conflicts over control of the spice trade. As the middle class grew during the Renaissance, the popularity of spices rose. Wars over the Indonesian Spice Islands broke out between expanding European nations and continued for about 200 years, between the 15th and 17th centuries.

The United States began its entry into the world spice industry in the 18th century, when American businessmen began their own spice companies and started dealing directly with Asian growers rather than the established European companies. When people started getting rich, more and more companies formed and soon there were hundreds of American ships making around-the-world voyages for spices. Americans made new contributions to the spice world, notably the creation of chili powder by Texas settlers as an easier way to make Mexican dishes and the development of techniques for dehydrating onions and garlic.

As spices became more common, their value began to fall. The trade routes were wide open, people had figured out how to transplant spice plants to other parts of the world, and the wealthy monopolies began to crumble.

Pepper and cinnamon are no longer luxuries for most of us, and spices have lost the status and allure that once placed them alongside jewels and precious metals as the world’s most valuable items. But the incredible history remains, as does the wonderful variety of exotic flavours, colours and smells that made spices so valuable in the first place.